The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any other agency, organization, employer or company.

—by Rashad D. Grove

1998 was a transitional time in hip-hop. Still reeling from the after effects the East Coast vs. West Coast feuds that claimed the lives of both 2Pac Shakur and The Notorious B.I.G, hip-hop desperately needed an injection of new energy to take the culture in a new direction, and the year was packed with releases from new and established voices that would serve as a catalyst for a new era: DMX, Big Pun, Queen Latifah, Master P, A Tribe Called Quest, JAY-Z, Lauryn Hill, Redman and others. But arguably, the most impactful release of was Aquemini by OutKast.

By this time, OutKast had already occupied a prominent space in hip-hop as an iconoclastic group that pushed rap past its preconceived boundaries of genre and region. Their influence upon popular music was growing with the release of each album as the Southern street tales of Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik and the extra-terrestrial themed ATLiens were both critically acclaimed and commercially successful LPs. As they prepared to work on their newest project, they were maturing as human beings. They were no longer impressionable teenagers, but now Black men dealing with all the complexities that life had to offer like familial relationships, artistic evolution, the trappings of fame and success, and the discovery of their identity as both members of a group and as individuals.

From a creative standpoint, Big Boi and André 3000 were at the vanguard of experimental hip-hop and this project would be a continuation of that motif. Dre had begun testing his vocal abilities and was delving deeper into production. Big was developing a penchant for writing infectious hooks that were fashioning their songwriting process. Their intentionality was to create a project that would transcend their previous work and leave a long-lasting effect upon the fabric of hip-hop.

The result was a masterpiece, Aquemini, the third studio album in the OutKast canon, released on September 29, 1998—an epic day in hip-hop that also featured JAY-Z’s Vol. 2 Hard Knock Life, Mos Def and Talib Kweli’s …Are Black Star, A Tribe Called Quest’s The Love Movement, and Brand Nubian’s Foundation.

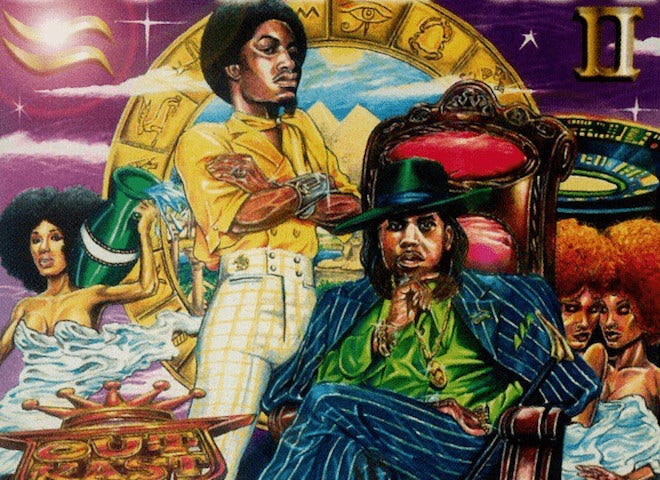

Initially conceived as the companion album to an uncompleted theatrical film, Aquemini—a portmanteau of the group members’ zodiac signs: Aquarius (Big Boi) and Gemini (André 3000)—is symbolic of the duo’s recurring theme of their differing personalities meshing into a cohesive musical offering. It’s an album built around the duality of Big Boi and Andre, a bridge that links their diverse artistic idiosyncrasies. But, sonically, Aquemini was as ground-breaking as any OutKast album. They expand upon their previous record’s outer space-inspired compositions by integrating live instrumentation, spoken word, and long instrumental segments that promoted their ideal of non-genre-conforming hip-hop.

It was their first project on which they handled most of the production duties with the assistance of their longtime Dungeon Family collaborators, Organized Noize and Mr. DJ, and the group used eclectic and soulful sounds incorporating elements of jazz, gospel, 70’s funk reggae, and even big band to score the album. From the lyrics, the production, and even the album sequencing, it’s a significant body of work.

Aquemini opens with the introductory track “Hold On, Be Strong,” a brief but beautiful mediation, a hymn of preparation of sorts that is reminiscent of interludes from Earth, Wind & Fire albums. (Dre even plays the kalimba on the track, channeling the spirit of Maurice White.) “Return of the ‘G” follows, on which Dre denounces those who were questioning his alternative style and street credibility: “The question is, ‘Big Boi, what’s up with Andre? / Is he in a cult? Is he on drugs? Is he gay? / When y’all gon’ break up?’ When y’all gon’ wake up? / N—a I’m feelin’ better than ever what’s wrong with you?” Lyrically, with provocative insight, they set the tone for remainder of the album.

Though one of the LP’s most popular songs is the harmonica-driven hoe-down “Rosa Parks,” another, the Raekwon-assisted, lyrical onslaught “Skew it On The Bar-B,” marked the first time a non-Dungeon Family MC made an appearance on an OutKast track. Raekwon’s Shaolin slang meshes seamlessly with the Dirty South funk of OutKast, foreshadowing how Southern hip-hop would deeply influence New York rap music in the coming years. In contrast to the crunk-funk of those two tracks is the laid-back soul of the title track, its chorus serving as the mission statement for album. The hook empathically states, “Even the sun goes down, heroes eventually die / Horoscopes often lie and sometimes ‘why’/ Nothin’ is for sure, nothin’ is for certain, nothin’ lasts forever / But until they close the curtain / It’s him and I, Aquemini.” It’s a fitting ode to their creative partnership.

While every song is captivating in its own way—including the cautionary tales of “Da Art Of Storytelling (Part I)” and the space funk odyssey “SpottieOttieDopaliscious” (a three-part story of the perils of Atlanta nightlife, an ill-fated romance, and the abyss of hopelessness)—there is something undeniably magical, even mystical about the almost nine-minute gospel-spiritual “Liberation.” Featuring Erykah Badu, Cee-Lo, Big Rube, Joi, and Myrna “Skreechy Peach” Brown, they collectively conjure the spirits of the ancestors employing images of slavery signifying the quest for artistic freedom.

Aquemini accomplished all that OutKast had hoped for. It was a commercial success—peaking at No. 2 on the Billboard charts on its way to a double-platinum certification—and is often considered by critics and fans alike as OutKast’s finest effort. With organic chemistry and imaginative musicality, Big and Dre elevated their artistry, setting the stage for their brand of Afro-futuristic hip-hop, and blazed a trail for both risk-taking sounds that defied labels and for eccentric artists to follow.

Its influence is apparent in Kanye West’s 808’s and Heartbreak, Drake’s So Far Gone and Janelle Monáe’s Electric Lady, in how they approached their songwriting, their means of production, and their visual presentations. And it created a blueprint for the likes of Cee-Lo Green and Childish Gambino to pursue their own unique visions with reckless abandon. (In fact, Young Thug and Lil Uzi Vert are likely widely accepted in the mainstream despite their nontraditional appearance because of OutKast’s example.)

Aquemini revealed how MCs could progress as musicians, their artistic palates could evolve, and the masses could be moved by creative ingenuity, ultimately transforming the scope of popular Black music.

More by Rashad D. Grove: